Manufacturers Index

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

| Featured Pianos | Piano Company Profiles |

| Pianos We've Restored |

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO CELEBRATE BEING IN BUSINESS DOING WHAT WE LOVE FOR 50 YEARS

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO CELEBRATE BEING IN BUSINESS DOING WHAT WE LOVE FOR 50 YEARS

— SINCE 1974 —

REGISTERED PIANO TECHNICIAN

— SINCE 1982 —

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

| Featured Pianos | Piano Company Profiles |

| Pianos We've Restored |

Albert Weber started a piano company in New York City that became a well respected and prosperous business. For historical memory the Weber name and many others, like Ernst Gabler, Frederick Mathushek and George Steck, as well as other names like Behning and Fischer would probably be names all piano enthusiasts would be familiar with if it weren't for the Steinway Company. Steinway has eclipsed many names then known for their outstanding old world craft skills in cabinet making and piano making.

Albert Weber started a piano company in New York City that became a well respected and prosperous business. For historical memory the Weber name and many others, like Ernst Gabler, Frederick Mathushek and George Steck, as well as other names like Behning and Fischer would probably be names all piano enthusiasts would be familiar with if it weren't for the Steinway Company. Steinway has eclipsed many names then known for their outstanding old world craft skills in cabinet making and piano making.

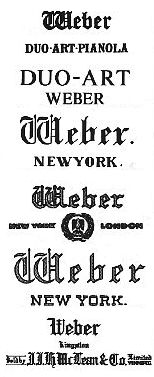

Many names, like Weber were finally assumed by other name-purchasing companies like the Aeolian Piano Company. Weber & Company was in fact finally purchased by Aeolian.

In the history of Weber piano company, there is an interesting rumor thread. Arthur Loesser writes about rumors that less expensive pianos with the Weber name were not actually made by Weber & Company at all. Apparently there were no charges made or proof to the claims circulating at the time. Loesser suggests malicious competitors or disgruntled employees might have been the ones spreading the rumors. It's fairly impossible to uncover obscure facts like that now, over a century later.

The intense advertising wars -- what Loesser calls "artist-concert-testimonial advertising" -- between the top companies during the later part of the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries was extremely expensive to anyone forced to play such a ruthless advertising game (even today the top companies spend an incredible amount of money on advertising). Weber & Company responded to the whirlwind effect Steinway & Sons was having on the industry. Both Albert Weber and his son fought hard to stay in the game. Ultimately, the Weber name would fall into obscurity. Nevertheless, the Weber piano name holds promise for restoration and repair. Many of them are known to be good pianos, worthy of refurbishing.

Michael Sweeney's piano rebuilding company is in West Chester, PA, just blocks from the historic West Chester University. Sweeney has been in business for over thirty years, and many of the recipients of the benefits of Sweeney's craft work have been music students, people going to college studying music, music theory, instrumentation, teaching music, and music performance, many of which were piano performance students of local schools like West Chester University and the Curtis Institute.

The various ways in which students become interested in specific topics within the field of music are themselves varied and interesting. A student might be set up to take a class because it's a requirement, not knowing what the course is really about or why it's required for the major, then something in the student's life will fall into a relationship with what's being taught that semester, the logic and theory of musical events. Of course, as students, we look for connections and relations between things. We search for meaning, then give papers on what to say about the human interaction with sound that becomes a musical expression.

While his Weber grand piano was being restored, the student continued on with the very last semester of theory courses. One was to fulfill a three course concentration in music theory, and in this class there was a discussion about how the clarinet's sound is sometimes compared to early reed and pump organs. Someone in class insisted that the comparison was only legitimate in a very limited way, that clarinets are a much more respected instrument, an instrument for professional musicians, and a reason for this is that clarinets can be tuned. "Old reed organs are always out of tune," she said, "that's why they don't make them anymore. They go out of tune and you're stuck. There's no one to tune them. Same with old pianos."

This made the piano student take notice. "Why the same thing with old pianos?" he asked.

"They get to a point where they no longer stay in tune. They wear out. Good tuners will refuse to tune them knowing that they'll immediately go out of tune. Clarinets are not always out of tune. A good clarinetist can play the clarinet in tune."

This argument didn't square with the piano student, but he began to worry. Was it a waste of money to send the piano to a shop for refurbishing? Would the piano come back from the shop sounding any better than it does now? Are old pianos necessarily antiquated, something only a collector of antiques would love, pleasant for birthday songs and Auld Lang Synes, but not something worth its restoration? Or would the piano come back to life through restorative work? Would it be able to stay in tune? Would it be worth the time and expense to tune it?

Having never known this particular Weber grand piano, there was no memory of how good the piano was in its earlier years, or any other intimate experience with the Weber piano name. Still, the student spoke up in class attempting to explain what he thought to be a worthy explanation as to why this Weber piano should be completely restored, rather than refinishing just the cabinet, which was certainly beautiful just under the temporal scars to justify the process of refinishing the cabinet. His reason was that the piano was simply worth much more (culturally and monetarily) as a working, living piano than it would be as an antique. An antique Weber piano would only be a shell of its former self. He asked the professor after class whether this old Weber piano would be worth an attempt at repair and rebuilding.

The professor told the student that it all depended upon the actual piano. "All pianos are individuals," the professor said. "You need someone who knows how to rebuild them to take a good look at it."

Later, after consulting with professional piano rebuilders, the student decided to have the piano rebuilt on the inside and refinished on the outside because he was reassured that the materials that went to make this Weber were of the highest quality and worthy of restoration. The wood used for the soundboard and structural frame of the cabinet and the beautiful old veneers for the cabinet were all American grown old growth and they looked in fairly good shape. In need of work, but in fairly good shape.

The student thought of other instruments that were built long ago and yet were in the finest of shape, alive as can be and ready to be played by the best of musicians. This Weber grand piano could be this way too. It felt like something possible; looking at the piano's sturdy cabinet, and being aware that all instruments must be maintained over time by people who know what they' are doing, it was time to get the piano some professional help.

"I want this piano to be like new again, like the fine instruments that are passed from generation to generation as if they have magical powers." And during the discussion about clarinets and reed organs, he spoke up saying that it isn't simply a clarinet being played in tune by the musician. It's also that the clarinet needs to be protected. It needs to repaired when it gets injured and rebuilt when it needs an overhaul.

It was rare that the craft of piano rebuilding becomes a topic of discussion in the typical college music department. Piano repair and rebuilding is something that goes on behind the scenes. For the most part it's an invisible trade. And yet, so needed in the fields of art and music.

The professor commended the student for considering the influence that the technician brings to the center of a musical occasion, like a performance. "The technician, both in repairing the instrument and in tuning it is a part of the performance. There is a trace not only in the tuning, but in the piano's ability to stay in tune."

This discussion was exciting for the student. This Weber piano that was newly his and being restored for his intimate approach to the study of music took on a different meaning. The next question in class was, "What does it really mean to be in tune?"

Little did the student know, but the theory teacher already had a plan, and after finding a way to let the question present itself, went on to spend half a semester exploring the logical, mathematical, philosophical implications of this strange, but interesting question about the ontology of intonation.

1954. Arthur Loesser, Men, Women and Pianos; A Social History. Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

1972. Alfred Dolge, Pianos and their Makers: A Comprehensive History of the Development of the Piano. Dover Publications, Inc., New York.

2001. Edwin M Good, Giraffes, Black Dragons and Other Pianos; A Technological History from Cristofori to the Modern Concert Grand. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

| Featured Pianos | Piano Company Profiles |

| Pianos We've Restored |